ROSY BEYELSCHMIDT

Strategies against oblivion

The task of art

is not to reproduce what is visible

but to render visible.

» Paul Klee «

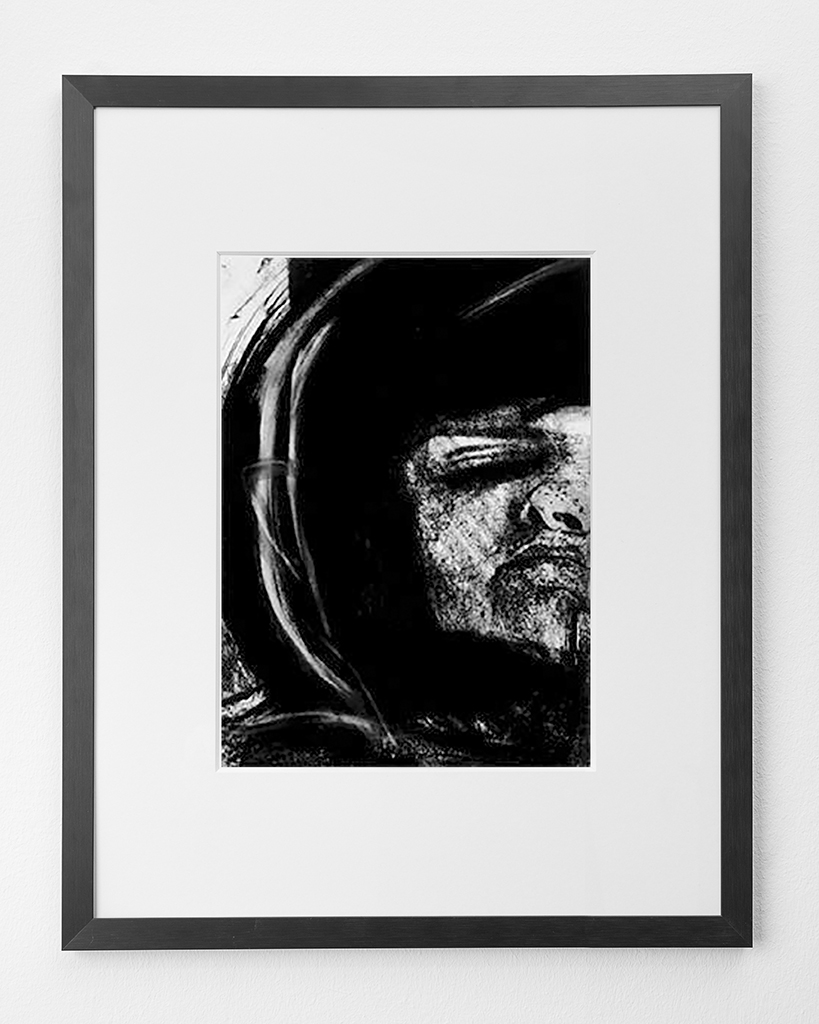

Rosy Beyelschmidt's large-format black-and-white photographs resist rapid, superficial approaches. Indeed, they require intense scrutiny and a careful quest for the subject. It is only when we have looked at them for some time, with concentration, that contours resolve from out of what are largely zones of dark or light, and parts of bodies or objects become recognisable: a hand, an arm, a knee, a head, the arm of a chair, a table, a step, a curtain or a coat. As we progressively make out what is there, we experience a sense of spatial depth, established by the techniques of overlayering and superimposition; though in fact no spatial continuum is created. Our attempt to associate these enigmatic visual structures with a reality external to the picture comes to nothing.The multifarious relations of the identifiable fragments of reality, in combination with further forms that appear abstract, open up associative spaces that touch upon the reality within us. In this way the photographs prompt an encounter with our own past. Their fragmentary character sets in train a process of remembering which might ideally bring repressed material back to the surface, and at all events will make us aware of the nature of the capacity to recall.

In adopting this approach, Rosy Beyelschmidt occupies a position contrary to current definitions of the photographic art such as that provided by the French philosopher Roland Barthes when distinguishing photography from painting. In contradistinction to the imitations practised by painting, says Barthes, in photography there is no denying the prior existence of the subject. Photography links reality and the past; and since this specific delimitation exists only here, it must (thus Barthes) be considered the essence of photography and its sensory content. The intent in photography, Barthes claims, focusses neither on art nor on communication but on referentiality. Referential credibility, and the related authenticity of the visual subject, constitute the fundamental principles of photography in Barthes' view. By contrast, what is unique in Rosy Beyelschmidt's work and specific to it resides in those very aspects of photography that Barthes considers secondary: their character as art, and their aim to communicate, even through the successive relinquishing of referential relations.

Most certainly Rosy Beyelschmidt's work is anchored in photographically documented reality. Her point of departure lies both in photographs taken by herself and in found photographic material - items chanced upon at flea markets, for instance. Often the photographs are of people in everyday situations, in the street or in interiors: a person sitting on a chair or descending a staircase, in an old people's home or in a hospital. The artist detaches these images from their original contexts, however, subjecting the material she works on to a protracted process of artistic transformation, clarifying and condensing and heightening the visual impact, selecting individual visual components, at times combining a number of images, amalgamating them into photographic syntheses and in this way metamorphosing her material step by step into photographic originals, into works that bear the hallmark of uniqueness. She avails herself of various technical strategies: re-photographed images, double exposures, superimposition using slide projectors or epidiascopes, or lamps of various kinds to produce different lighting effects. At times she treats the paper with fire or a flame. It is as if the darkroom were a room of light in which she transmutes the material she starts with into impressive pictorial visions. Once the reworking process is finished, it is scarcely possible to make any statements at all concerning the origin or meaning of the images used. When visual material is semantically encoded, the relation of sign to signified becomes less exact; the referential nexus starts to dissolve. With a logical consistency, Rosy Beyelschmidt refuses to give her works explanatory titles. She prefers not to direct the viewer's individual associations towards preconceived ideas about possible meanings or content.

Beyelschmidt had the idea for this particular approach to the photographic medium when she was using a photocopier in the course of earlier work. At that time she was making photocopied self- portraits from her own face, in quest of the unconscious, the forgotten, the repressed. She pressed her face onto the glass plate of the machine and then worked up the results by hand. The character studies that resulted were expressive and bizarre, radical interrogations of the self that recalled the grimacing heads of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt or Arnulf Rainer's overpainting. Rosy Beyelschmidt then turned from the light source of the photocopying machine to the room of light that her studio offered. She still uses her body there in arranging the various sources of light: "I create scenarios by installing specific visual material in the projectors and then projecting it to suit my purposes in the action, moving about the space myself to a fixed plan. By moving and standing still and by the continuous repetition of actions, my body becomes an abstract, forgotten shape, and under the ceaseless projection of images in light it is perceived either entire or only in fragments, or it is absorbed into the light, no longer perceptible, only to be intuited." The artist included her own body in earlier work, but in the photographs she does now it is no longer to be seen.

The black-and-white photographs on exhibition in the Gothaer Kunstforum were created especially for the show. They are suited to the architecture of the space; so on one side there are large-format images (160 x 127 cm) and on the other somewhat smaller-format pieces (132 x 109 cm). As Thomas Sternberg has shown, the limitation to black and white, and the almost infinite range of shades of grey, means for Rosy Beyelschmidt a concentration on fundamental qualities of the visual image, focussing on nuanced gradations of light, contrast and composition.

The "subjects" of her visual world have not undergone any change in these recent works. Here too, careful and patient and at times almost strenuous scrutiny will make out fragments of the body or of objects: a child's hand that appears to be clutching at scaffolding or a seat but nonetheless grasps at vacancy, an arm lying at rest, an elbow crossed over by austere dark shapes and above it threatening equipment that may be pliers or equestrian gear, in the background the gleaming white shape of an apron; then again, an interior with the backrest of a chair or the edge of a table, or a piece of floral- pattern material that may be part of a curtain. One might continue, but the point is that two rather different effects can be observed: there are images that have an implicitly menacing character, and there are others that partake of the nature of a still life. Rosy Beyelschmidt, if asked about the original visual material in its unprocessed state, is perfectly happy to provide information. But what do the supposedly "real" stories behind the images mean? What information am I in fact in possession of if I know that the puzzling gear was in fact braces for trousers, or that the white apron was the coat of a doctor standing at the side of a patient in a barred bed, or that one interior image shows part of a stove and the curtain behind it is in fact the wallpaper? The intentions behind Rosy Beyelschmidt's work lies on a quite different level. She wants the foreground of the original photograph to recede; her aim is to reveal possible backgrounds through a process of defamiliarization. How might the story have gone? Beyelschmidt herself compares the individual processes involved in the artistic labour, perceived in the final result as spatial layering or gradation, with step-by-step discovery of "truth" behind a facade, penetrating into unconscious realms, the location of emotional states and the retrieval of repressed memories. Revelation by concealment, the investigation of one's own self and that of the persons portrayed (who stand for any and every one), is one of the chief spurs to her work as an artist. In the images there are components that suggest loneliness, uncertainty and a sense of having been deserted. The recurring motif of bars implies imprisonment in an impenetrable world. But at the same time the images occasion "the rediscovery of self, and a wary empathy with others ... To take cognisance of another requires a calm approach, a careful and gentle enquiry into what is concealed behind the appearance." (Thomas Sternberg.) The fragmentary nature of her works seems of importance to Rosy Beyelschmidt, for even the recollection of forgotten or repressed feelings makes only a tentative and fragmented appearance.

And so, in the tension between ready identification of things and the dissolution of those things by aesthetic means, we encounter an opulent interplay of delicate visual structures. These are at odds with the current culture of rapid visual stimulus and gratification familiar not only from photographic images but also from their derivatives in film, television and video. The element of media criticism in Rosy Beyelschmidt's work invites the drawing of parallels with the first generation of video artists in the late Sixties and early Seventies, who slowed down the sequence of images and deliberately dispensed with plot and editorial cutting, thus burlesquing and challenging the ways in which television was consumed. Quite apart from the circumstance that Beyelschmidt has done video installations as well as photography, her work can be historically seen in the tradition of the avant-garde photographers of the 20th century who attempted to fix photograph images of the sensitive, the invisible and the unconscious. The work of Edward Steichen and Gertrude Käsebier might be named in this connection, as might the "Schadographs" of Christian Schad, the photograms of László Moholy- Nagy and Man Ray, or the subjective photography of an Otto Steinert. The highly individual and contemporary aesthetics of Rosy Beyelschmidt have re-articulated that tradition.

Bettina Ruhrberg ©

Gothaer Kunstforum, Cologne/Germany, 1998

(English translation: Michael Hulse)

-

INSTALLATION

PAINTING

<PHOTO>

SOUND

VIDEO

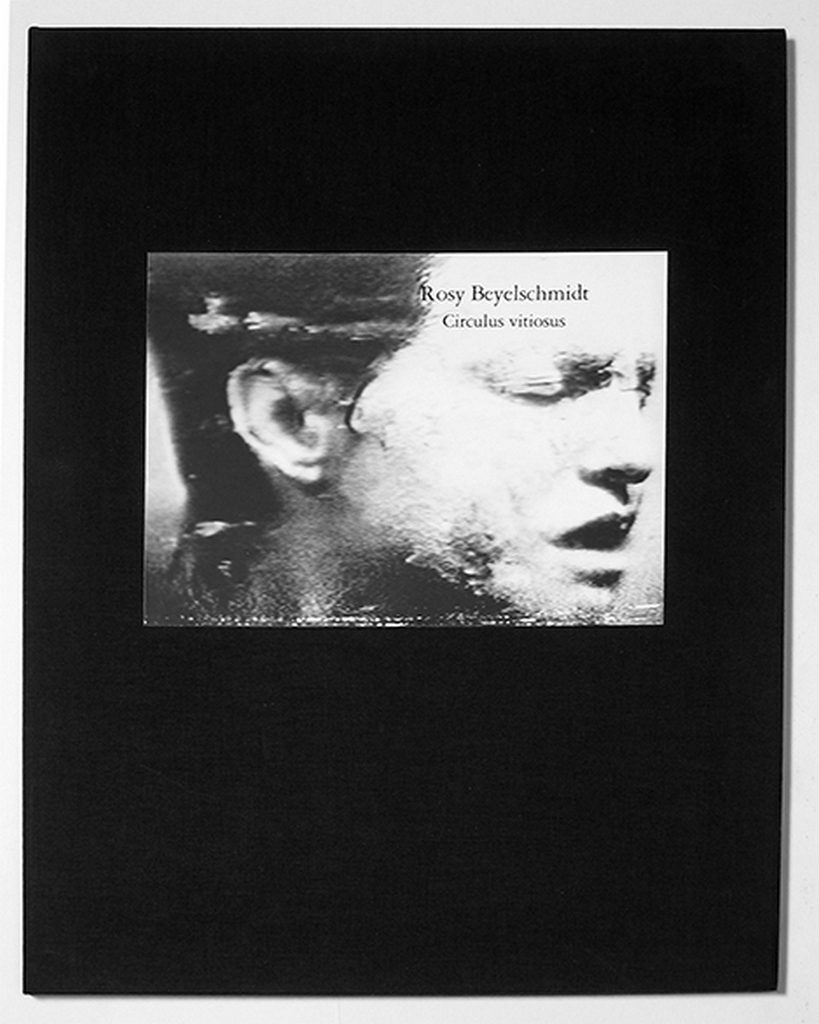

PUBLICATION

Strategies against oblivion

The task of art

is not to reproduce what is visible

but to render visible.

» Paul Klee «

Rosy Beyelschmidt's large-format black-and-white photographs resist rapid, superficial approaches. Indeed, they require intense scrutiny and a careful quest for the subject. It is only when we have looked at them for some time, with concentration, that contours resolve from out of what are largely zones of dark or light, and parts of bodies or objects become recognisable: a hand, an arm, a knee, a head, the arm of a chair, a table, a step, a curtain or a coat. As we progressively make out what is there, we experience a sense of spatial depth, established by the techniques of overlayering and superimposition; though in fact no spatial continuum is created. Our attempt to associate these enigmatic visual structures with a reality external to the picture comes to nothing.The multifarious relations of the identifiable fragments of reality, in combination with further forms that appear abstract, open up associative spaces that touch upon the reality within us. In this way the photographs prompt an encounter with our own past. Their fragmentary character sets in train a process of remembering which might ideally bring repressed material back to the surface, and at all events will make us aware of the nature of the capacity to recall.

In adopting this approach, Rosy Beyelschmidt occupies a position contrary to current definitions of the photographic art such as that provided by the French philosopher Roland Barthes when distinguishing photography from painting. In contradistinction to the imitations practised by painting, says Barthes, in photography there is no denying the prior existence of the subject. Photography links reality and the past; and since this specific delimitation exists only here, it must (thus Barthes) be considered the essence of photography and its sensory content. The intent in photography, Barthes claims, focusses neither on art nor on communication but on referentiality. Referential credibility, and the related authenticity of the visual subject, constitute the fundamental principles of photography in Barthes' view. By contrast, what is unique in Rosy Beyelschmidt's work and specific to it resides in those very aspects of photography that Barthes considers secondary: their character as art, and their aim to communicate, even through the successive relinquishing of referential relations.

Most certainly Rosy Beyelschmidt's work is anchored in photographically documented reality. Her point of departure lies both in photographs taken by herself and in found photographic material - items chanced upon at flea markets, for instance. Often the photographs are of people in everyday situations, in the street or in interiors: a person sitting on a chair or descending a staircase, in an old people's home or in a hospital. The artist detaches these images from their original contexts, however, subjecting the material she works on to a protracted process of artistic transformation, clarifying and condensing and heightening the visual impact, selecting individual visual components, at times combining a number of images, amalgamating them into photographic syntheses and in this way metamorphosing her material step by step into photographic originals, into works that bear the hallmark of uniqueness. She avails herself of various technical strategies: re-photographed images, double exposures, superimposition using slide projectors or epidiascopes, or lamps of various kinds to produce different lighting effects. At times she treats the paper with fire or a flame. It is as if the darkroom were a room of light in which she transmutes the material she starts with into impressive pictorial visions. Once the reworking process is finished, it is scarcely possible to make any statements at all concerning the origin or meaning of the images used. When visual material is semantically encoded, the relation of sign to signified becomes less exact; the referential nexus starts to dissolve. With a logical consistency, Rosy Beyelschmidt refuses to give her works explanatory titles. She prefers not to direct the viewer's individual associations towards preconceived ideas about possible meanings or content.

Beyelschmidt had the idea for this particular approach to the photographic medium when she was using a photocopier in the course of earlier work. At that time she was making photocopied self- portraits from her own face, in quest of the unconscious, the forgotten, the repressed. She pressed her face onto the glass plate of the machine and then worked up the results by hand. The character studies that resulted were expressive and bizarre, radical interrogations of the self that recalled the grimacing heads of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt or Arnulf Rainer's overpainting. Rosy Beyelschmidt then turned from the light source of the photocopying machine to the room of light that her studio offered. She still uses her body there in arranging the various sources of light: "I create scenarios by installing specific visual material in the projectors and then projecting it to suit my purposes in the action, moving about the space myself to a fixed plan. By moving and standing still and by the continuous repetition of actions, my body becomes an abstract, forgotten shape, and under the ceaseless projection of images in light it is perceived either entire or only in fragments, or it is absorbed into the light, no longer perceptible, only to be intuited." The artist included her own body in earlier work, but in the photographs she does now it is no longer to be seen.

The black-and-white photographs on exhibition in the Gothaer Kunstforum were created especially for the show. They are suited to the architecture of the space; so on one side there are large-format images (160 x 127 cm) and on the other somewhat smaller-format pieces (132 x 109 cm). As Thomas Sternberg has shown, the limitation to black and white, and the almost infinite range of shades of grey, means for Rosy Beyelschmidt a concentration on fundamental qualities of the visual image, focussing on nuanced gradations of light, contrast and composition.

The "subjects" of her visual world have not undergone any change in these recent works. Here too, careful and patient and at times almost strenuous scrutiny will make out fragments of the body or of objects: a child's hand that appears to be clutching at scaffolding or a seat but nonetheless grasps at vacancy, an arm lying at rest, an elbow crossed over by austere dark shapes and above it threatening equipment that may be pliers or equestrian gear, in the background the gleaming white shape of an apron; then again, an interior with the backrest of a chair or the edge of a table, or a piece of floral- pattern material that may be part of a curtain. One might continue, but the point is that two rather different effects can be observed: there are images that have an implicitly menacing character, and there are others that partake of the nature of a still life. Rosy Beyelschmidt, if asked about the original visual material in its unprocessed state, is perfectly happy to provide information. But what do the supposedly "real" stories behind the images mean? What information am I in fact in possession of if I know that the puzzling gear was in fact braces for trousers, or that the white apron was the coat of a doctor standing at the side of a patient in a barred bed, or that one interior image shows part of a stove and the curtain behind it is in fact the wallpaper? The intentions behind Rosy Beyelschmidt's work lies on a quite different level. She wants the foreground of the original photograph to recede; her aim is to reveal possible backgrounds through a process of defamiliarization. How might the story have gone? Beyelschmidt herself compares the individual processes involved in the artistic labour, perceived in the final result as spatial layering or gradation, with step-by-step discovery of "truth" behind a facade, penetrating into unconscious realms, the location of emotional states and the retrieval of repressed memories. Revelation by concealment, the investigation of one's own self and that of the persons portrayed (who stand for any and every one), is one of the chief spurs to her work as an artist. In the images there are components that suggest loneliness, uncertainty and a sense of having been deserted. The recurring motif of bars implies imprisonment in an impenetrable world. But at the same time the images occasion "the rediscovery of self, and a wary empathy with others ... To take cognisance of another requires a calm approach, a careful and gentle enquiry into what is concealed behind the appearance." (Thomas Sternberg.) The fragmentary nature of her works seems of importance to Rosy Beyelschmidt, for even the recollection of forgotten or repressed feelings makes only a tentative and fragmented appearance.

And so, in the tension between ready identification of things and the dissolution of those things by aesthetic means, we encounter an opulent interplay of delicate visual structures. These are at odds with the current culture of rapid visual stimulus and gratification familiar not only from photographic images but also from their derivatives in film, television and video. The element of media criticism in Rosy Beyelschmidt's work invites the drawing of parallels with the first generation of video artists in the late Sixties and early Seventies, who slowed down the sequence of images and deliberately dispensed with plot and editorial cutting, thus burlesquing and challenging the ways in which television was consumed. Quite apart from the circumstance that Beyelschmidt has done video installations as well as photography, her work can be historically seen in the tradition of the avant-garde photographers of the 20th century who attempted to fix photograph images of the sensitive, the invisible and the unconscious. The work of Edward Steichen and Gertrude Käsebier might be named in this connection, as might the "Schadographs" of Christian Schad, the photograms of László Moholy- Nagy and Man Ray, or the subjective photography of an Otto Steinert. The highly individual and contemporary aesthetics of Rosy Beyelschmidt have re-articulated that tradition.

Bettina Ruhrberg ©

Gothaer Kunstforum, Cologne/Germany, 1998

(English translation: Michael Hulse)